Addressable vs. Conventional Fire Alarm Systems: Key Differences for Ontario Projects

Selecting the right fire alarm system is a foundational decision in the life-safety design of any building. Whether you are planning a new development, renovating an existing facility, or upgrading aging equipment, the choice between an addressable and a conventional (zone-based) fire alarm system affects design coordination, installation complexity, long-term maintenance, and how efficiently an incident can be managed. In Ontario, these systems must be designed and installed to align with applicable codes and standards, and they must be compatible with the building’s use, size, and risk profile.

This article outlines how each system works, where each is typically appropriate, and the practical considerations property owners, developers, architects, and contractors should weigh when planning fire alarm scope.

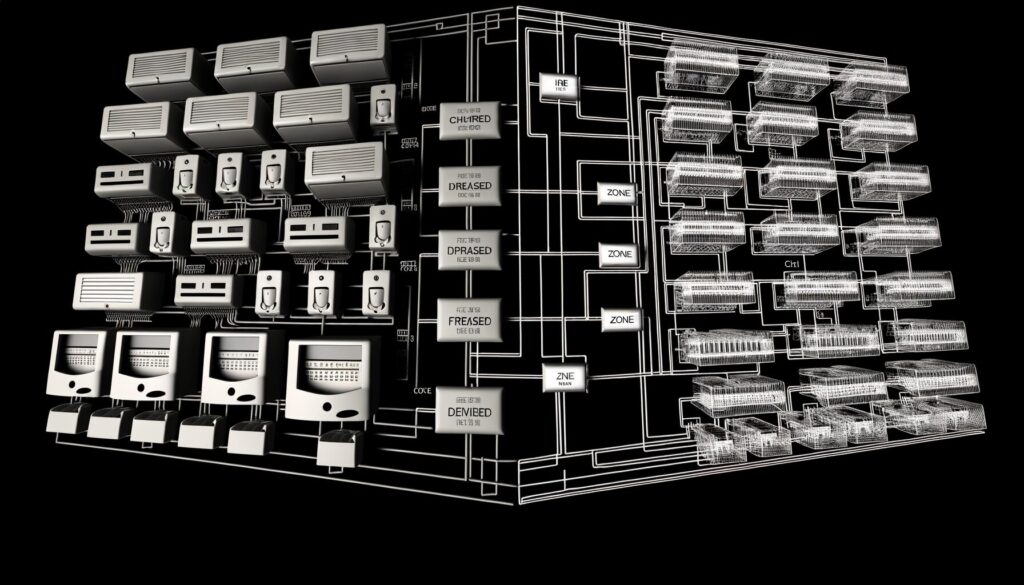

How Conventional (Zone-Based) Fire Alarm Systems Work

A conventional fire alarm system groups initiating devices—such as smoke detectors, heat detectors, and manual pull stations—into “zones.” Each zone is wired back to the fire alarm control unit (FACU). When a device activates, the panel identifies the zone in alarm, not the specific device. The annunciator and panel display will typically indicate something like “Zone 3 Alarm,” after which responding staff or firefighters locate the source within that zone.

Typical characteristics of conventional systems

- Zone indication: The panel identifies the zone, not the exact device address.

- Wiring layout: Devices are wired in circuits per zone, often resulting in more home-run wiring in larger buildings.

- Simplified equipment: Conventional panels and devices can be straightforward for smaller projects.

- Maintenance approach: Troubleshooting may require more time because the system identifies a general area rather than a precise location.

Where conventional systems are commonly used

Conventional systems are often well-suited to smaller buildings with limited device counts and simple layouts, where zoning is easy to understand and where rapid pinpoint identification is less critical. Examples may include small commercial spaces, basic industrial ancillary buildings, or low-complexity facilities—subject to code requirements and the building’s classification.

How Addressable Fire Alarm Systems Work

An addressable fire alarm system assigns a unique “address” to each initiating device and, often, each module controlling functions such as relay outputs, door holders, elevators, or smoke control interfaces. Devices communicate with the control unit over a signaling line circuit (SLC). When a device activates, the panel identifies the exact device and its programmed description—for example, “Smoke Detector – Level 5 East Corridor.” This level of detail can improve emergency response and reduce investigation time during alarms and troubles.

Typical characteristics of addressable systems

- Point identification: The panel indicates the exact device, enabling faster incident location.

- Efficient wiring: SLC loop topology can reduce overall wiring compared to multi-zone home runs, especially in larger buildings.

- Advanced diagnostics: Many systems provide device sensitivity monitoring, history logs, and detailed trouble reporting.

- Flexible programming: Cause-and-effect sequences can be tailored for phased evacuation, voice communication, and complex interfaces.

Where addressable systems are commonly used

Addressable systems are frequently selected for multi-storey residential buildings, mixed-use developments, long-term care facilities, larger commercial properties, and buildings with complex life-safety integration. They are also common where there are requirements for detailed annunciation, multiple risers, distributed annunciators, elevator interface, smoke control coordination, or integrated emergency voice communication systems.

Key Comparison Factors for Ontario Property and Construction Teams

1) Speed of identification and response

In an emergency, reducing time to locate the initiating device matters. Conventional systems identify a zone; addressable systems identify a specific device. In larger buildings—such as apartment towers, retirement residences, or multi-tenant commercial spaces—point identification can significantly improve response efficiency for both building staff and fire services.

2) Design coordination and system integration

Modern buildings often require the fire alarm system to interface with other systems and building components, such as:

- Elevator recall and shunt trip coordination

- Automatic door releases and magnetic hold-opens

- Smoke control and ventilation shutdown

- Fire pump and sprinkler supervisory monitoring

- Emergency voice communication and paging

While either system type can support certain interfaces, addressable platforms typically provide more flexibility and clarity when implementing detailed sequences of operation and annunciation. This can reduce ambiguity during commissioning and future modifications.

3) Construction impacts: wiring, labour, and phasing

Conventional systems can be economical for smaller footprints, but the wiring can become extensive as device counts increase—especially when many zones are needed to maintain intelligible coverage. Addressable SLC loops often reduce cable quantity and can simplify routing, which may help in high-rise construction where riser space and pathway coordination are critical.

For phased occupancy, renovations, or additions, addressable systems can be easier to expand with minimal disruption. However, careful planning is still required to maintain code-compliant coverage and to avoid overloading loops or power supplies.

4) Troubleshooting, maintenance, and lifecycle management

Property owners often experience the difference between these systems most clearly during service calls. With conventional systems, a “zone trouble” may require more on-site investigation to identify the exact device or segment. Addressable systems can report an individual device trouble, dirty detector warnings, or intermittent communication issues with more precision.

That said, addressable systems are more dependent on correct programming and documentation. Accurate device labels, as-built drawings, and updated sequences of operation are essential, particularly when tenant improvements or suite reconfigurations occur.

5) Code compliance, documentation, and commissioning

Fire alarm work in Ontario involves more than selecting hardware. The design must align with the applicable edition of the Ontario Building Code, referenced standards (commonly including CAN/ULC requirements), and the intended building use. The final installation typically requires verification, commissioning, and coordination with other disciplines (mechanical, electrical, architectural) to confirm that interfaces function as intended.

For both conventional and addressable systems, clarity in zoning/annunciation, device locations, audibility, and emergency power requirements should be established during design—not left to site decisions. Addressable systems, with their greater programmability, also benefit from well-defined cause-and-effect documentation to reduce change orders and site rework.

Choosing the Right System: Practical Guidance

There is no universal best choice. A conventional system may be appropriate for smaller, uncomplicated buildings with stable layouts and limited device counts. An addressable system is often advantageous where scale, complexity, and long-term adaptability are important. Decision-makers should consider:

- Building size and number of devices: Larger buildings tend to benefit from addressable identification and wiring efficiencies.

- Complex interfaces: Projects with smoke control, elevator integration, or voice systems often align well with addressable platforms.

- Future changes: If tenant turnover or renovations are expected, addressable systems can simplify expansions and reprogramming.

- Operations and maintenance resources: The value of detailed diagnostics increases when in-house staff or service providers rely on quick fault isolation.

- Budget and lifecycle view: Upfront cost is only one factor; downtime, service calls, and future modifications can change the total cost of ownership.

Conclusion

Addressable and conventional fire alarm systems can both meet life-safety objectives when properly designed, installed, and verified for the specific building and occupancy. The right choice depends on project complexity, operational needs, and how the building may evolve over time. For Ontario projects, engaging engineering consulting support can help clarify code-driven requirements, define sequences of operation, and coordinate fire alarm scope with architectural and building systems to support a clear path from design through commissioning.